Dress Detective: Dating a Victorian Wedding Dress

- Ashley Webb

- Feb 9, 2022

- 6 min read

Continuing with the topic of 1870s vs 1880s garments from my last post, I wanted to share some construction details of a dress recently acquired by the Historical Society of Western Virginia (my full-time gig). Originally worn by Emma Plunkett sometime in the 1860s at her wedding to Nathan Hunter, the dress includes several characteristics of being modified to conform to changing silhouettes as dictated by society.

While we do have some provenance on the dress to help us give the piece a round about date, there's still not a lot. Although I can't figure out who Emma's parents are, I do know Emma was born around 1843, making her about 17 in 1860. She married Nathan Hunter, son of Washington Hunter and Susan Harvey. Nathan was a dentist, and he and Emma moved to Texas sometime between 1860 and 1876, where Nathan died. Emma moved back to Virginia, where she met and married a Mr. Hunt (I believe this is George Hunt of Prince Edward County) sometime after 1885. All Appomattox county records, except for land tax books, were burned in 1892 when the courthouse caught fire, and we therefore have no records of when Emma married either Nathan or Mr. Hunt. Emma died in 1903 at the age of 60. She gifted this dress to her step-daughter, Florine Hunt Fowler, with the statement that this was part of her trousseau at her wedding to Nathan.

Based off this family history, we know the dress was worn sometime between 1860 and 1892 (when the courthouse burned). I would hope that her parents wouldn't marry her off any earlier than 17, which is why I've placed that as a start date. But, there are further clues to help us date it.

Being able to read a dress can identify its silhouette - further narrowing a date, can help determine whether a garment is actually vintage, and can tell you if the dress has been modified.

Two great books on the methods I'll be using are:

The Dress Detective: A Practical Guide to Object-based Research by Ingrid Mida and Alexandra Kim

How to Read a Dress: A Guide to Changing Fashion from the 16th to 20th Century by Lydia Edwards

While having an extant garment right in front of you is, of course, the best option possible, you can still use these methods to date photographs or even photographs of extant garments (hello, museum collections!).

The first thing you notice with this dress is the vibrant blue of the silk. Before 1856, most dyes used to give fabric their color derived from plants such as indigo, woad, madder, brazilwood, turmeric and others, animals such as shellfish purple and cochineal, and minerals. A young chemist named William Henry Perkins discovered a vibrant purple dye by accident when attempting to create a chemically identical, artificial version of quinine. Instead, he discovered what he called 'Tyrian purple' - a combination of aniline (an extract of coal tar) and other compounds. This discovery pushed others to identify chemical makeups of other vibrant colors as well, revolutionizing the synthetic commercial dye industry. The blue of this dress, also called Nicholson's blue, was discovered by Edward Chambers Nicholson in 1862.

This information on synthetic dyes now pushes the start date to 1862. There's still more though. Let's look at the silhouette:

The drop shoulders of the bodice, the overall elliptical shape of the front of the skirt to the longer train at the back, and the buttons which stop at the waist all emanate from the 1860s.

I did some census digging to corroborate what I was seeing. I discovered that Nathan, Emma, and their two sons were living in Chariton, Missouri, in 1870. The oldest son, Wurt [sic], was listed as 3 years old, placing their marriage sometime between 1862 (the discovery date of the blue aniline dye) and at least 1866.

This dress, while being made for a trousseau for the mid-1860s, received a transformation to make it stay relevant with the changing fashions of the period.

At first glance, the elongated vertical seams at the waist make it look like it's a princess cut bodice. If you read my last blog post, you'll know that in my extant garment research of the Met's collections, the mid 1870s ushered in a 'natural form' silhouette, which utilized princess seams to create elongated cuirass bodices. Instead of adding darts to a bodice to shape it, princess cut bodices utilized shaped panels to create the shape, which cinched in at the waist and extended down over the hips.

Up close though, you see there is a waist seam, with the seams along the bottom of the peplum matching closely (but not perfectly) to the darts of the bodice. You can see this the most in the image below at the far right seam near the buttonholes of the bodice, where everything doesn't quite match up.

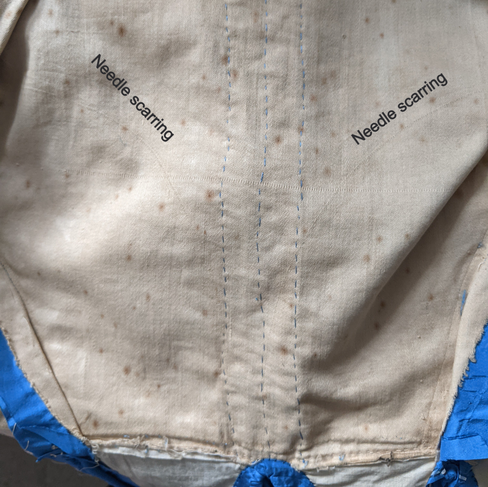

When examining the interior of the bodice, there's a whole slew of things that also point to this.

There is an apparent waist seam which would not be there if it in fact was a dress made in the early 1870s. As I mentioned, the seams above and below the waist seam don't quite line up, and the lining of the bottom half of the bodice is a different cotton than the top half of the bodice.

Additionally, there's needle scarring along the inside of the lining at the back of the bodice, as well as along the base of the peplum. Needle scarring happens when you remove the threads from the fabric and the needle holes become visible. The peplum also has heavy creases from where it was sewn originally and then altered.

Although it's not very evident, I also think the sleeves were cut down to be more fashionable, as well. There is a bit of extra fabric on the inside of one of the cuffs, making me think the sleeves might have been cut down. There's also needle scarring and cartridge pleating there, too. Perhaps the sleeves had some pleated pagoda sleeves? While fun to image, I don't think that is actually a thing :D

While it's evident that a lot changed on the bodice, the skirt has been sneakily refashioned.

There is needle and fold scarring to the front of the waistband, and the placement of the pocket odd. I'm not exactly sure how the skirt would have originally been fashioned, but the folds along the waistband look like cartridge pleats, but that is more of an 1850s trait. The large knife pleats are seen more heavily in 1860s garments, and this skirt is flat along the front instead of knife pleated all the way around the circumference of the waistband. At some point the skirt was taken apart and the flat front created. Additionally, the pocket, in a seam at the right proper side of the skirt, sits forward into the flat front - an odd spot for a pocket. Another reason the skirt was most likely taken apart and panels moved.

The ruffles are not original to the dress and came at a later date. They're all machine sewn and added to the garment by hand, whereas the seams to the skirt itself are hand sewn with both basting stitches and small running stitches. When the skirt was refashioned, I'm wondering if the extra material cut off was placed onto the bodice to create the peplum as well as to create the ruffles. The evidence of both the cartridge pleat scars on both the waistband of the skirt and at the bottom of the peplum points to this being the case.

With some minor changes to the orientation of the panels and the addition of the ruffles, the skirt on the whole wasn't changed that much. Most of the skirt's fullness was rearranged to be pulled toward the back to create that soft, high bustle. This means the dress was refashioned sometime between 1869 and 1876 when the first bustle period effectively ended putting this dress hopelessly out of fashion and into a wardrobe.

In conclusion, this dress was handsewn most likely by Emma for her wedding, sometime between 1864-1866 (I'm assuming here that it takes about two years for the blue to get on the market, in to mass production, and then finally in to the consumer's hands). It was then refashioned between 1869-1874 - probably more on the earlier side of the 1870s than the later, since in 1876 the bustle disappears. I hope you enjoyed this object based case study, and happy investigating!

Thanks to Como wedding photographer Wezoree, looking for the ideal wedding photographer in Como has never been more simple. Couples may investigate reviews, price comparisons, and browse amazing portfolios all at one spot using a well chosen collection of 76 gifted photographers. The simple layout of the site lets one easily seek and make direct contacts with experts, therefore saving important time during wedding preparation. Wezoree makes it easy to locate the perfect match whether your taste is for a traditional design or something more contemporary. Anyone organizing a wedding in Como will find this tool revolutionary!